Difference between revisions of "Talk:250a Microcontroller & Sensors Lab Pd"

(→Download Lab) |

(→Putting It All Together) |

||

| (67 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<font size=5>Lab 2: Microcontroller and Sensors</font><br> | <font size=5>Lab 2: Microcontroller and Sensors</font><br> | ||

| − | + | See [https://ccrma.stanford.edu/courses/250a/schedule.html this quarter's schedule] for due dates. | |

| − | For this lab you need your [https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~eberdahl/Satellite Satellite CCRMA] kit. | + | For this lab you need your [https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~eberdahl/Satellite Satellite CCRMA] kit. It is important that you have some time to focus on the final part of the lab "Putting It All Together." This is why some parts of the lab are optional. |

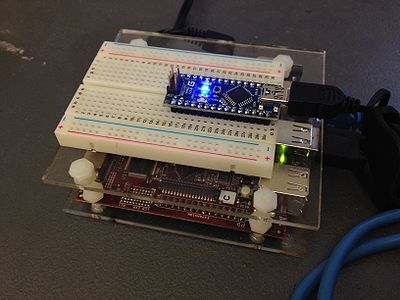

== Mount Arduino And Bread Board == | == Mount Arduino And Bread Board == | ||

| − | * Mount the bread board on your | + | * Mount the bread board on your acrylic as shown in the picture below, so that the higher numbered rows are facing the USB and ethernet ports. |

* Insert your Arduino Nano into the bread board all the way at the end toward the higher numbered rows and seated roughly in the middle (see below). | * Insert your Arduino Nano into the bread board all the way at the end toward the higher numbered rows and seated roughly in the middle (see below). | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:EmptySatellite2.jpg|400px]] |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

== Download Lab == | == Download Lab == | ||

* Use the same procedure as [https://ccrma.stanford.edu/wiki/Software_Lab_250 described before] to power up Satellite CCRMA and login as the user ''ccrma'' with the password ''temppwd''. | * Use the same procedure as [https://ccrma.stanford.edu/wiki/Software_Lab_250 described before] to power up Satellite CCRMA and login as the user ''ccrma'' with the password ''temppwd''. | ||

| − | * | + | * You need to download the lab2 files to the memory card in your Satellite CCRMA kit. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | * You can first download the archived files to your laptop by clicking here: [https://ccrma.stanford.edu/courses/250a/labs/lab2.zip], and then you can install and setup [http://cyberduck.ch/ CyberDuck] as shown in class and use it to copy ''lab2.zip'' to your kit. (Alternatively, if you are a power user, you can try to share your laptop's Internet connection with the kit and then use ''wget'') | |

| − | * Extract the ZIP file by typing "unzip | + | * Extract the ZIP file by typing "unzip lab2.zip". |

== Prepare Arduino == | == Prepare Arduino == | ||

| Line 54: | Line 45: | ||

* Select ''Arduino Nano w/ ATMega328'' under Tools->Board and ''/dev/ttyUSB0'' under Tools->Serial Port. Then hit the Play button to verify and compile the program. | * Select ''Arduino Nano w/ ATMega328'' under Tools->Board and ''/dev/ttyUSB0'' under Tools->Serial Port. Then hit the Play button to verify and compile the program. | ||

| − | * Upload the Firmata firmware to your Arduino Nano using upload button, the fourth square button from the left (the one with the sideways arrow). | + | * Upload the Firmata firmware to your Arduino Nano using upload button, the fourth square button from the left (the one with the sideways arrow). If you watch the RX and TX lights on the Arduino carefully, you will "see" the data flow over the serial USB link into the Arduino as the firmware is uploaded. |

| + | |||

| + | * Close the Arduino program by closing all of the Arduino windows. (This is important because it frees up the USB serial port so that Pd can talk to the Arduino board later. Pd and the Arduino software will not share the Arduino Nano device at the same time.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| − | |||

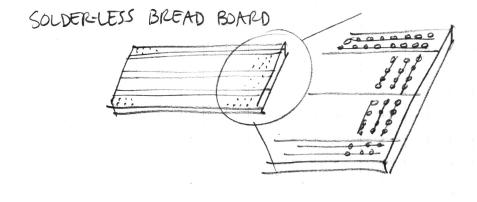

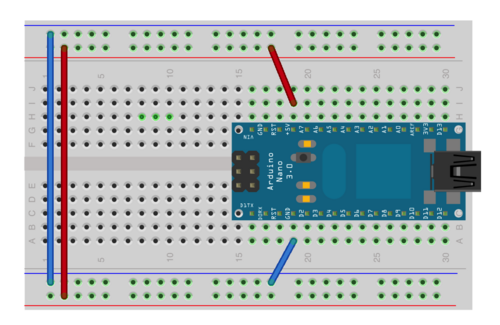

== Routing Power On The Breadboard == | == Routing Power On The Breadboard == | ||

| Line 66: | Line 60: | ||

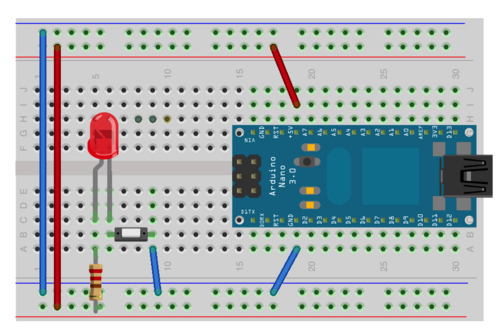

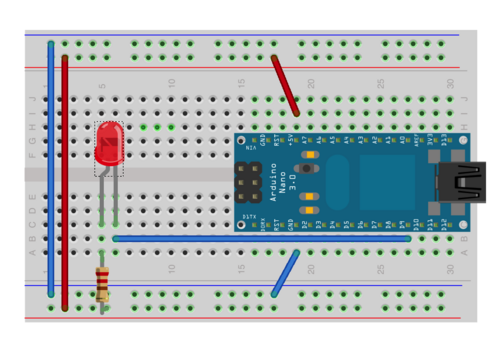

* Now connect jumper wires as shown in the image below so that the upper and lower long columns can serve as a power supply for your future circuits. | * Now connect jumper wires as shown in the image below so that the upper and lower long columns can serve as a power supply for your future circuits. | ||

| − | * Connect a short jumper from | + | * Connect a short jumper from the GND pin of the Arduino to the blue column. |

| − | * Connect a short jumper from | + | * Connect a short jumper from the 5V pin of the Arduino to the red column. |

* Finally, use two longer jumpers to connect together the blue columns and the red columns as shown below: | * Finally, use two longer jumpers to connect together the blue columns and the red columns as shown below: | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:0.png|500px]] |

* Check your wires now to make sure that you did it correctly! | * Check your wires now to make sure that you did it correctly! | ||

* Now plug the USB cable back into the Arduino. You should see the blue light come back on on the Arduino. ('''If you don't, you have a short circuit!''' In other words, somehow you connected the wires together incorrectly, effectively connecting the 5V and the GND pins of the Arduino together. Unplug the USB cable again immediately and fix the circuit! '''Short circuits are big no-nos because they can (and often do!) destroy the Arduino.''' This is why we recommend unplugging the USB cable while you are changing your circuit.) | * Now plug the USB cable back into the Arduino. You should see the blue light come back on on the Arduino. ('''If you don't, you have a short circuit!''' In other words, somehow you connected the wires together incorrectly, effectively connecting the 5V and the GND pins of the Arduino together. Unplug the USB cable again immediately and fix the circuit! '''Short circuits are big no-nos because they can (and often do!) destroy the Arduino.''' This is why we recommend unplugging the USB cable while you are changing your circuit.) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

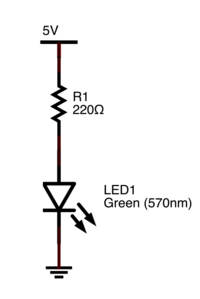

== Buttons, Switches and LEDs == | == Buttons, Switches and LEDs == | ||

| Line 90: | Line 81: | ||

Optional: Use the digital multimeter to check the voltage at A0. Set it to the direct current voltage "DVC" scale at 20V. On the multimeter, connect the black probe to COM and the red probe to V-Ohm-mA. Connect the other end of the black probe to ground and the red probe to the A0 wire. Also optional: Use the digital multimeter to find out what the "5V" supply actually is. | Optional: Use the digital multimeter to check the voltage at A0. Set it to the direct current voltage "DVC" scale at 20V. On the multimeter, connect the black probe to COM and the red probe to V-Ohm-mA. Connect the other end of the black probe to ground and the red probe to the A0 wire. Also optional: Use the digital multimeter to find out what the "5V" supply actually is. | ||

| + | |||

| Line 99: | Line 91: | ||

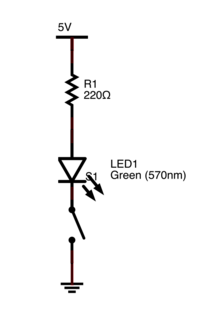

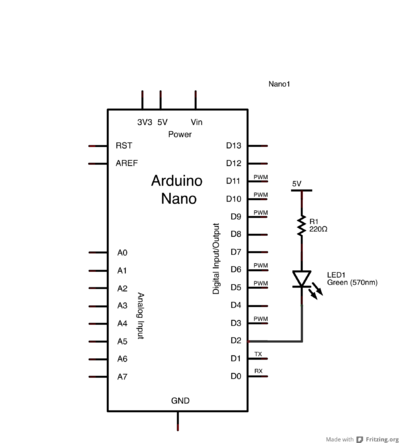

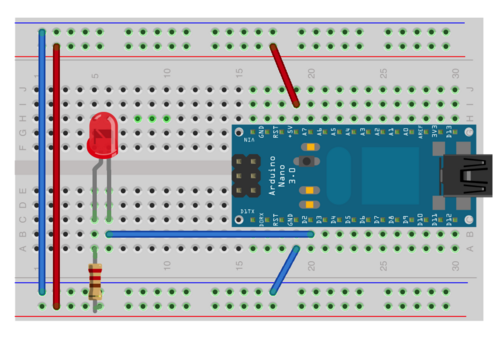

* In the third example, we'll replace the manual switch with an Arduino pin (set to output mode), so we can control the LED from our program. | * In the third example, we'll replace the manual switch with an Arduino pin (set to output mode), so we can control the LED from our program. | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:1a_schem.png|200px]] [[Image:1b_schem.png|200px]] [[Image:1c_schem.png|400px]] |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

==== Power a LED (always on) ==== | ==== Power a LED (always on) ==== | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:1a.png|500px]] |

Build the following circuit on your breadboard. Use a 220 Ohm resistor (red red brown gold -- see [http://wiki.xtronics.com/index.php/Resistor_Codes this page] about resistor color codes). | Build the following circuit on your breadboard. Use a 220 Ohm resistor (red red brown gold -- see [http://wiki.xtronics.com/index.php/Resistor_Codes this page] about resistor color codes). | ||

| Line 109: | Line 104: | ||

Because the LED is a diode, it has a set voltage drop across the leads; exceeding this causes heat to build up and the LED to fail prematurely. So! It is always important to have a resistor in series with the LED. | Because the LED is a diode, it has a set voltage drop across the leads; exceeding this causes heat to build up and the LED to fail prematurely. So! It is always important to have a resistor in series with the LED. | ||

| − | Also, another consequence of the LED being a diode is that it has directionality. The longer lead, the anode, should be connected towards power; the shorter, cathode, should be connected towards ground. (In the | + | Also, another consequence of the LED being a diode is that it has directionality. The longer lead, the anode, should be connected towards power (THE LONG ARM REACHES FOR POWER!!!); the shorter, cathode, should be connected towards ground. (In the diagram, the longer lead has a bent "knee.") |

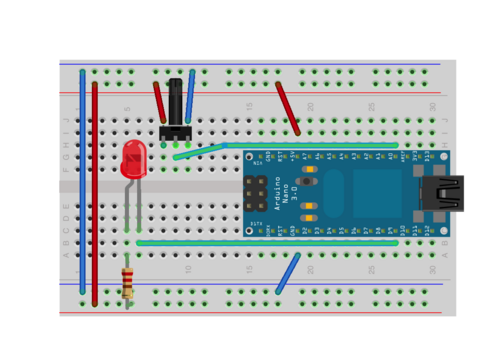

==== Make a light switch ==== | ==== Make a light switch ==== | ||

| − | |||

Next, we'll insert a switch into the circuit. The momentary switches in your kit are "normal open", meaning that the circuit is interrupted in the idle state, when the switch is not pressed. Pressing the switch closes the circuit until you let go again. | Next, we'll insert a switch into the circuit. The momentary switches in your kit are "normal open", meaning that the circuit is interrupted in the idle state, when the switch is not pressed. Pressing the switch closes the circuit until you let go again. | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:1b.png|500px]] |

Use a multimeter to see what happens to the voltage on either side of the LED when you press the switch. | Use a multimeter to see what happens to the voltage on either side of the LED when you press the switch. | ||

==== Toggling LED with Pd ==== | ==== Toggling LED with Pd ==== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:1c.png|500px]] | |

| − | [[Image: | + | |

In the third example, we'll replace the manual switch with an Arduino pin (set to output mode), so we can control the LED from our program. The safe way to do this is to let the Arduino pin sink current - if we toggle the pin low, it acts as ground and current flows through the resistor and the LED as it did in the previous examples. When we take the pin high, to 5V, there is no potential difference and no current flows - the LED stays off. | In the third example, we'll replace the manual switch with an Arduino pin (set to output mode), so we can control the LED from our program. The safe way to do this is to let the Arduino pin sink current - if we toggle the pin low, it acts as ground and current flows through the resistor and the LED as it did in the previous examples. When we take the pin high, to 5V, there is no potential difference and no current flows - the LED stays off. | ||

| − | * | + | * Open the arduinoLab.pd patch, which should be in the directory lab2. |

| + | * First look in the pd message window. Probably you will observe some errors. | ||

| + | * To get pd to connect properly to the Arduino Nano, you need to correctly select the serial port # (see the upper left-hand portion of the patch). This functionality allows you to address multiple Arduino Nano's connected at the same time. Right now we only have one. Try selecting different serial port #'s until you see a message like "[comport] opened serial line device 4 (/dev/ttyUSB0)." | ||

| + | * Verify now that communication with the Arduino Nano is working by turning on and off digital output 13. This pin is wired directly to an orange LED on the Arduino, so you can easily "see" the state of the pin. | ||

| + | * Go to the "digital pin data direction" pane and set pin 2 to ''output''. | ||

| + | * Then go back to the "digital outputs" pane. When you click on the checkbox for digital pin 2, the state of the LED should change (on vs. off). | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!-- | ||

| + | * There are a lot of options in the patch. We have prepared some exercise presets (see the upper right-hand corner) to try to make it easier for you. | ||

| + | * Press the "toggling LED with software" button in the upper right to preset the outputs properly. The patch expects you to connect the LED to digital pin 2 (D2). (Hint: You can look inside the preset by double clicking on "pd toggling_LED_with_software.") --> | ||

| Line 131: | Line 133: | ||

=== Sensing buttons in software === | === Sensing buttons in software === | ||

| − | |||

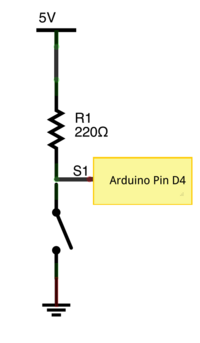

We've used code to trigger output - what about the other direction, sensing physical input in code? Just as easy. Here is a simple switch circuit: | We've used code to trigger output - what about the other direction, sensing physical input in code? Just as easy. Here is a simple switch circuit: | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image: Button1_schem.png|200px]] |

| + | [[Image:Button1.png|600px]] | ||

| + | <!-- Nicer image but with longer breadboard and different row numbers [[Image: Lab2-6.jpg]] --> | ||

When the switch is open, the Arduino pin (set to input mode) is pulled to 5V - in software, we'll read Arduino.HIGH. When the switch is closed, the voltage at the Arduino pin falls to 0V - in software, we'll read Arduino.LOW. The pull-up resistor is used to limit the current going through the circuit. In software, we can check the value of the pin and switch between graphics accordingly. | When the switch is open, the Arduino pin (set to input mode) is pulled to 5V - in software, we'll read Arduino.HIGH. When the switch is closed, the voltage at the Arduino pin falls to 0V - in software, we'll read Arduino.LOW. The pull-up resistor is used to limit the current going through the circuit. In software, we can check the value of the pin and switch between graphics accordingly. | ||

| − | * In the ArduinoLab patch, press the "sensing buttons in software" button to preset the outputs properly. The patch expects you to connect the switch to digital pin 4 (D4). | + | * Setup the circuit and connect it to digital pin 4 (D4). |

| + | * Although the "digital pin data direction" in the pd patch shows that D4 is set to input by default, actually it is not! To change this, first set D4 to output and then change it back to input. | ||

| + | * Then look at the "digital input readings" pane while you press the button. <!--But you will notice that the pin 4 reading does not change! | ||

| + | * This is because the corresponding digital input port needs to be enabled. In other words, even if you set a pin to input, you need to also enable the inputs for that ''port''. Each port is mapped to eight pins. Because pin D4 is part of the first eight pins, you should enable port zero in the "enable digital input ports" pane. | ||

| + | * Now --> | ||

| + | When you press the button, you should see the digital pin 4 reading change in the "digital input readings" pane. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <!-- * In the ArduinoLab patch, press the "sensing buttons in software" button to preset the outputs properly. The patch expects you to connect the switch to digital pin 4 (D4). --> | ||

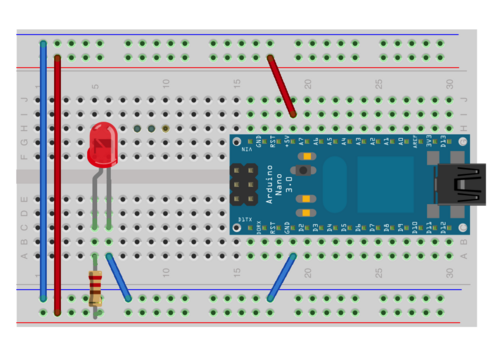

| − | === Fading | + | === Fading LED (Optional) === |

| + | What about those "breathing" LEDs on Mac Powerbooks? The fading from bright to dim and back is done using pulse-width modulation (PWM). In essence, the LED is toggled on and off rapidly, say 1000 times a second, faster than your eye can follow. The percentage of time the LED is on (the duty) controls the perceived brightness. To control an LED using PWM, you'll have to connect it to one of the pins that support PWM output - 3,5,6, 9, 10 or 11 on the Arduino. Then write a patch that cycles the PWM values. | ||

| − | + | For instance, for a single LED connected to pin D9: | |

| + | * Connect the LED to pin D9 of the Arduino using the usual circuit. | ||

| + | * In ArduinoLab.pd, set pin D9 to pwm in the "digital pin data direction" pane. | ||

| + | * In the pane for "pwm/servo outputs," choose pin 9. | ||

| + | * Pull the "analog_output" horizontal slider back and forth and watch the LED get brighter and dimmer. | ||

| + | * Fun extension: Get an RGB (red/green/blue) LED, connect it to digital pins 9, 10, and 11, and adjust the brightness of the three color components to cycle the LED through a rainbow of colors '''(see very end of this page)'''! | ||

| + | <!-- | ||

* In the ArduinoLab patch, press the "Fading LEDs" button to preset the outputs properly. The patch expects you to connect the LED to digital pins 9-11 (D9-11). | * In the ArduinoLab patch, press the "Fading LEDs" button to preset the outputs properly. The patch expects you to connect the LED to digital pins 9-11 (D9-11). | ||

| − | * In your Arduino Kit, you have a RGB LED which has four leads (it's white when not lit); it's basically like 3 LEDs sharing the same ground. Use PWM and this [[http://blog.ncode.ca/?p=38 pin out information]] to make the LED cycle through a rainbow of colors. | + | * In your Arduino Kit, you have a RGB LED which has four leads (it's white when not lit); it's basically like 3 LEDs sharing the same ground. Use PWM and this [[http://blog.ncode.ca/?p=38 pin out information]] to make the LED cycle through a rainbow of colors. --> |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image: Fading led.png|500px]] | |

| + | == Using Analog Sensors == | ||

Now we will work with the continuous input values provided by analog sensors - potentiometers, accelerometers, distance rangers, etc. | Now we will work with the continuous input values provided by analog sensors - potentiometers, accelerometers, distance rangers, etc. | ||

| − | |||

| + | |||

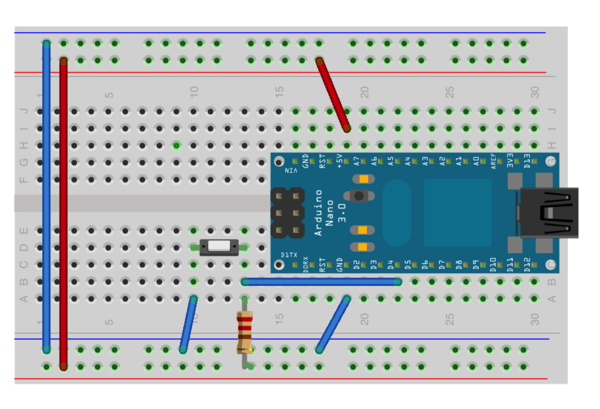

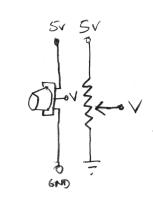

| + | === Make a Light Dimmer === | ||

In this example we'll build a light dimmer: a knob connected to a light so that when you turn the knob, the light increases or decreases in brightness. We'll use a potentiometer. The potentiometer has three terminals - the resistance between the first and the third terminal is constant (10k Ohms in our case). The resistance between terminals 1 and 2 (and between 2 and 3) varies as you turn the shaft of the potentiometer. If you apply 5V to terminal 1, connect terminal 3 to Ground, you will get a continuously varying voltage at terminal 2 as you turn the shaft (Why that is the case will become clearer once you've learned about voltage dividers further below). | In this example we'll build a light dimmer: a knob connected to a light so that when you turn the knob, the light increases or decreases in brightness. We'll use a potentiometer. The potentiometer has three terminals - the resistance between the first and the third terminal is constant (10k Ohms in our case). The resistance between terminals 1 and 2 (and between 2 and 3) varies as you turn the shaft of the potentiometer. If you apply 5V to terminal 1, connect terminal 3 to Ground, you will get a continuously varying voltage at terminal 2 as you turn the shaft (Why that is the case will become clearer once you've learned about voltage dividers further below). | ||

| Line 161: | Line 180: | ||

* In the ArduinoLab patch, press the "Light Dimmer" button to preset the outputs properly. The patch expects you to connect the LED to digital pin 9 (D9) and the potentiometer to analog pin 0 (A0). Use the PWM controls under output controls in the ArduinoLab patch to control the lightness and dimness of the LED. | * In the ArduinoLab patch, press the "Light Dimmer" button to preset the outputs properly. The patch expects you to connect the LED to digital pin 9 (D9) and the potentiometer to analog pin 0 (A0). Use the PWM controls under output controls in the ArduinoLab patch to control the lightness and dimness of the LED. | ||

| + | [[Image: Dimmer_bb.png|500px]] | ||

| + | * Optional: hook up two LEDs, one red one green. as you turn in one direction, red gets brighter; in the other, green gets brighter. In the middle, both are off. | ||

| + | <!-- === Drawing a graph of analog input === | ||

| + | Let's understand better what the values are that we are reading from the analog input. To do so, we will use a slider graph to show how the analog values are changing in time. | ||

| + | Leave the potentiometer part of your circuit, you may take off the LED part if you want to. Use A0 or A1 to graph the analog input in the ArduinoLab patch. --> | ||

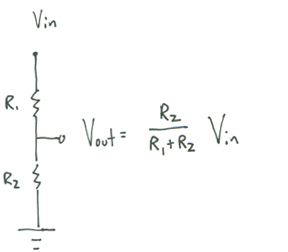

| − | + | === Voltage Dividers === | |

| + | In your kit, the potentiometer, IR distance ranger, and accelerometer are especially easy to work with since they directly output a changing voltage that can be read by one of Arduino's analog input pins. | ||

| − | |||

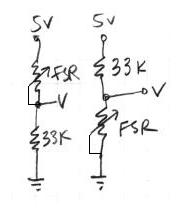

| − | + | Other sensors don't give you a varying output voltage per se, but instead change their resistance. Examples in your kit are the force sensitive resistor (FSR) and the bend or flex sensor. It is easy to get a changing voltage based on a changing resistance through a voltage divider circuit ([http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voltage_divider Wikipedia page]). The idea is that you put two resistors in series between power and ground: one that changes resistance (your sensor), and one of a known, fixed resistance. At the point in between the two resistors, you can measure how much the voltage has dropped through the first resistor. This value changes as the ratio of resistances between variable and fixed resistors change. More formally: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[Image:res_divider.png]] | |

| + | * potentiometer: | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Pot.png]] | |

| + | * force-sensitive resistor (FSR): | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:FSR.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Try both circuits. Test the resistance range of your sensor. If you want 2.5 volts to be the middle, make the comparison resistor (33k in the diagram) the "average" value of the FSR's resistance. Test this with a multimeter. | ||

| + | |||

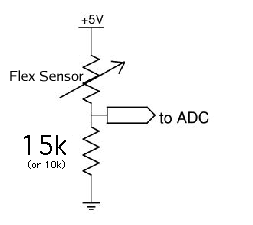

| + | * Bend Sensor | ||

| + | [[Image:Bend_sensor.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Thresholding with a Range Sensor (Optional) === | ||

Thresholding is the process of turning continuous data into a discrete yes/no decision. | Thresholding is the process of turning continuous data into a discrete yes/no decision. | ||

| Line 185: | Line 222: | ||

Let's do something useful with that data. Imagine a smart cookie jar that reminds you not to snack in between meals. We could put an IR ranger into the lid. Whenever a hand comes too close, our program could play a warning sound or flash a warning light. Write a patch to manage this! | Let's do something useful with that data. Imagine a smart cookie jar that reminds you not to snack in between meals. We could put an IR ranger into the lid. Whenever a hand comes too close, our program could play a warning sound or flash a warning light. Write a patch to manage this! | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | === Tilt control with an Accelerometer (Optional) === | ||

| + | In this example, we'll simulate the motion of a ball on a tilting plane in software and control the tilt through a sensor. Think of it as a first step to build your own electronic game of Labyrinth. The right sensor to use is an accelerometer. Accelerometers can report on both static and dynamic acceleration -- think of static acceleration as the angle the accelerometer is held with respect to the ground (the acceleration measured here is due to gravity). Dynamic acceleration occurs when you shake the sensor. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Mma7260qt-3-axis-accelerometer.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The accelerometer in your kit is a 3-axis, +/- 1.5-6g [http://shop.moderndevice.com/products/mma7260qt-3-axis-accelerometer accelerometer] sensor (1g is the acceleration due to gravity). You will have to solder on 0.1" header pins to fit this into the breadboard. The connections you need to make are Vin to 5V power from the Arduino , G to ground, and Xo, Yo & Zo to the first three analog input pins on the Arduino board. My default, the acceleration range is set to +/- 1.5g; you could solder on the gsel jumpers if you want less sensitive/greater range with +/- 6g. | ||

Now, get a feel for the data the accelerometer provides. Use the Light Dimmer presets, which will track analog values on A0 and A1. Then pick up the Arduino+accelerometer board and tilt it in various directions. Start by holding it so that the accelerometer board is parallel to the ground. Find in which direction the X reading increases and decreases; do the same for the Y reading. | Now, get a feel for the data the accelerometer provides. Use the Light Dimmer presets, which will track analog values on A0 and A1. Then pick up the Arduino+accelerometer board and tilt it in various directions. Start by holding it so that the accelerometer board is parallel to the ground. Find in which direction the X reading increases and decreases; do the same for the Y reading. | ||

| Line 197: | Line 236: | ||

Next, change the PD patch so that you can also read the Z axis of the accelerometer. | Next, change the PD patch so that you can also read the Z axis of the accelerometer. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | = Putting It All Together = | |

| + | * Create a patch to make sounds based on button and sensor values from the Arduino. You can try to adapt your patches from Lab 1, or come up with a new patch. | ||

| + | * Try to make a simple musical interaction. Think about music - | ||

| + | ** does it have dynamics? | ||

| + | ** can you turn the sound off? | ||

| + | ** can it be expressive? | ||

| − | + | * Make a video showing your interaction! Narrate over the video to explain your design. Post your video on the [[Music 250a Lab Video Wiki]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == (OPTIONAL) Light an RGB LED! == | |

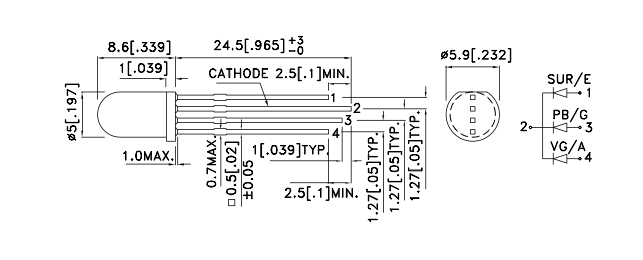

| − | + | Included in your kit is a common-cathod RGB LED. Unlike the other LEDs, this LED has four pins instead of two. By using the Pulse Width Modulation Control, you can get the led to cycle through different parts of the colors spectrum. | |

| − | + | Here is the schematic for the LED from the data sheet: | |

| − | + | [[File:RGB.png]] | |

| − | [[ | + | |

| + | You can see that the longest lead is the common cathode (which should go to ground). The each of the other pins should be powered from the Arduino (ideally through PWM-capable pins) through a low-value resistor (~220 Ohm). | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<center>[[250a 2010]]</center> | <center>[[250a 2010]]</center> | ||

[[Category:250a]][[Category:PID]] | [[Category:250a]][[Category:PID]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:28, 15 October 2012

Lab 2: Microcontroller and Sensors

See this quarter's schedule for due dates.

For this lab you need your Satellite CCRMA kit. It is important that you have some time to focus on the final part of the lab "Putting It All Together." This is why some parts of the lab are optional.

Contents

Mount Arduino And Bread Board

- Mount the bread board on your acrylic as shown in the picture below, so that the higher numbered rows are facing the USB and ethernet ports.

- Insert your Arduino Nano into the bread board all the way at the end toward the higher numbered rows and seated roughly in the middle (see below).

Download Lab

- Use the same procedure as described before to power up Satellite CCRMA and login as the user ccrma with the password temppwd.

- You need to download the lab2 files to the memory card in your Satellite CCRMA kit.

- You can first download the archived files to your laptop by clicking here: [1], and then you can install and setup CyberDuck as shown in class and use it to copy lab2.zip to your kit. (Alternatively, if you are a power user, you can try to share your laptop's Internet connection with the kit and then use wget)

- Extract the ZIP file by typing "unzip lab2.zip".

Prepare Arduino

- Now see which devices are attached to Linux by running the command following command. They will appear the be files. Wow, there are so many!

ls /dev

- To list only the serial interface devices type

ls /dev/tty*

- Now use the retractable USB cable to plug the Arduino into one of the USB ports of the Beagle Board. As the Arduino powers up, you should see some lights come on.

- Now run

ls /dev/tty*

again, and you should now see the new device /dev/ttyUSB0 appear also, which represents the Arduino Nano.

Troubleshooting: If you do not see /dev/ttyUSB0, then try rebooting using sudo reboot to see if that fixes this problem. (If you reboot, this will take about 45 seconds, and you will have to login again using ssh. If that doesn't work, come talk to us. If you are a Linux pro, you can try to debug the problem yourself by typing dmesg and looking at the result.)

- The next step is to install some simple firmware onto the Arduino so that it knows what we want it to do. Start the Arduino software in the terminal by typing

arduino &

- Open StandardFirmata from the Arduino software pull-down menus File|Examples|Firmata. Look at the program. This is what will control the Arduino.

- Select Arduino Nano w/ ATMega328 under Tools->Board and /dev/ttyUSB0 under Tools->Serial Port. Then hit the Play button to verify and compile the program.

- Upload the Firmata firmware to your Arduino Nano using upload button, the fourth square button from the left (the one with the sideways arrow). If you watch the RX and TX lights on the Arduino carefully, you will "see" the data flow over the serial USB link into the Arduino as the firmware is uploaded.

- Close the Arduino program by closing all of the Arduino windows. (This is important because it frees up the USB serial port so that Pd can talk to the Arduino board later. Pd and the Arduino software will not share the Arduino Nano device at the same time.)

Routing Power On The Breadboard

- When changing the circuit on the breadboard, it is a good idea to unplug the USB cable from the Arduino, so unplug it for now.

- Remind yourself about how the sockets on the breadboard are wired together:

- Now connect jumper wires as shown in the image below so that the upper and lower long columns can serve as a power supply for your future circuits.

- Connect a short jumper from the GND pin of the Arduino to the blue column.

- Connect a short jumper from the 5V pin of the Arduino to the red column.

- Finally, use two longer jumpers to connect together the blue columns and the red columns as shown below:

- Check your wires now to make sure that you did it correctly!

- Now plug the USB cable back into the Arduino. You should see the blue light come back on on the Arduino. (If you don't, you have a short circuit! In other words, somehow you connected the wires together incorrectly, effectively connecting the 5V and the GND pins of the Arduino together. Unplug the USB cable again immediately and fix the circuit! Short circuits are big no-nos because they can (and often do!) destroy the Arduino. This is why we recommend unplugging the USB cable while you are changing your circuit.)

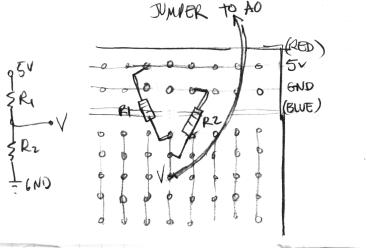

Buttons, Switches and LEDs

- Build the circuit that is detailed in the following figure. Use components and jumpers to construct your circuits on the solderless bread-board. Here's how to wire a simple 2-resistor circuit on the solderless bread-board (for example R1 = 10K, R2 = 10K):

Use the voltage divider equation to calculate hypothetically what A0 should be.

Optional: Use the digital multimeter to check the voltage at A0. Set it to the direct current voltage "DVC" scale at 20V. On the multimeter, connect the black probe to COM and the red probe to V-Ohm-mA. Connect the other end of the black probe to ground and the red probe to the A0 wire. Also optional: Use the digital multimeter to find out what the "5V" supply actually is.

Build the Button and LED Circuit

We'll start our tutorial with three simple light circuits.

- In the first one, the LED is permanently on.

- In the second, the LED only lights up when a button is pressed and a circuit is completed.

- In the third example, we'll replace the manual switch with an Arduino pin (set to output mode), so we can control the LED from our program.

Power a LED (always on)

Build the following circuit on your breadboard. Use a 220 Ohm resistor (red red brown gold -- see this page about resistor color codes).

Because the LED is a diode, it has a set voltage drop across the leads; exceeding this causes heat to build up and the LED to fail prematurely. So! It is always important to have a resistor in series with the LED.

Also, another consequence of the LED being a diode is that it has directionality. The longer lead, the anode, should be connected towards power (THE LONG ARM REACHES FOR POWER!!!); the shorter, cathode, should be connected towards ground. (In the diagram, the longer lead has a bent "knee.")

Make a light switch

Next, we'll insert a switch into the circuit. The momentary switches in your kit are "normal open", meaning that the circuit is interrupted in the idle state, when the switch is not pressed. Pressing the switch closes the circuit until you let go again.

Use a multimeter to see what happens to the voltage on either side of the LED when you press the switch.

Toggling LED with Pd

In the third example, we'll replace the manual switch with an Arduino pin (set to output mode), so we can control the LED from our program. The safe way to do this is to let the Arduino pin sink current - if we toggle the pin low, it acts as ground and current flows through the resistor and the LED as it did in the previous examples. When we take the pin high, to 5V, there is no potential difference and no current flows - the LED stays off.

- Open the arduinoLab.pd patch, which should be in the directory lab2.

- First look in the pd message window. Probably you will observe some errors.

- To get pd to connect properly to the Arduino Nano, you need to correctly select the serial port # (see the upper left-hand portion of the patch). This functionality allows you to address multiple Arduino Nano's connected at the same time. Right now we only have one. Try selecting different serial port #'s until you see a message like "[comport] opened serial line device 4 (/dev/ttyUSB0)."

- Verify now that communication with the Arduino Nano is working by turning on and off digital output 13. This pin is wired directly to an orange LED on the Arduino, so you can easily "see" the state of the pin.

- Go to the "digital pin data direction" pane and set pin 2 to output.

- Then go back to the "digital outputs" pane. When you click on the checkbox for digital pin 2, the state of the LED should change (on vs. off).

Optional: Try changing your patch so the light stays on when you press the mouse button, and stays off when you press it again. After that, change your patch so the light blinks on/off. Then, have your patch button switch the light between on and blinking.

Sensing buttons in software

We've used code to trigger output - what about the other direction, sensing physical input in code? Just as easy. Here is a simple switch circuit:

When the switch is open, the Arduino pin (set to input mode) is pulled to 5V - in software, we'll read Arduino.HIGH. When the switch is closed, the voltage at the Arduino pin falls to 0V - in software, we'll read Arduino.LOW. The pull-up resistor is used to limit the current going through the circuit. In software, we can check the value of the pin and switch between graphics accordingly.

- Setup the circuit and connect it to digital pin 4 (D4).

- Although the "digital pin data direction" in the pd patch shows that D4 is set to input by default, actually it is not! To change this, first set D4 to output and then change it back to input.

- Then look at the "digital input readings" pane while you press the button.

When you press the button, you should see the digital pin 4 reading change in the "digital input readings" pane.

Fading LED (Optional)

What about those "breathing" LEDs on Mac Powerbooks? The fading from bright to dim and back is done using pulse-width modulation (PWM). In essence, the LED is toggled on and off rapidly, say 1000 times a second, faster than your eye can follow. The percentage of time the LED is on (the duty) controls the perceived brightness. To control an LED using PWM, you'll have to connect it to one of the pins that support PWM output - 3,5,6, 9, 10 or 11 on the Arduino. Then write a patch that cycles the PWM values.

For instance, for a single LED connected to pin D9:

- Connect the LED to pin D9 of the Arduino using the usual circuit.

- In ArduinoLab.pd, set pin D9 to pwm in the "digital pin data direction" pane.

- In the pane for "pwm/servo outputs," choose pin 9.

- Pull the "analog_output" horizontal slider back and forth and watch the LED get brighter and dimmer.

- Fun extension: Get an RGB (red/green/blue) LED, connect it to digital pins 9, 10, and 11, and adjust the brightness of the three color components to cycle the LED through a rainbow of colors (see very end of this page)!

Using Analog Sensors

Now we will work with the continuous input values provided by analog sensors - potentiometers, accelerometers, distance rangers, etc.

Make a Light Dimmer

In this example we'll build a light dimmer: a knob connected to a light so that when you turn the knob, the light increases or decreases in brightness. We'll use a potentiometer. The potentiometer has three terminals - the resistance between the first and the third terminal is constant (10k Ohms in our case). The resistance between terminals 1 and 2 (and between 2 and 3) varies as you turn the shaft of the potentiometer. If you apply 5V to terminal 1, connect terminal 3 to Ground, you will get a continuously varying voltage at terminal 2 as you turn the shaft (Why that is the case will become clearer once you've learned about voltage dividers further below).

- Connect the middle pin of the potentiometer to analog input 0, the other two to +5V and ground.

- Through a 220Ohm resistor, connect an LED to pin 9(anode or long side to resistor, cathode to pin 9)

- In the ArduinoLab patch, press the "Light Dimmer" button to preset the outputs properly. The patch expects you to connect the LED to digital pin 9 (D9) and the potentiometer to analog pin 0 (A0). Use the PWM controls under output controls in the ArduinoLab patch to control the lightness and dimness of the LED.

- Optional: hook up two LEDs, one red one green. as you turn in one direction, red gets brighter; in the other, green gets brighter. In the middle, both are off.

Voltage Dividers

In your kit, the potentiometer, IR distance ranger, and accelerometer are especially easy to work with since they directly output a changing voltage that can be read by one of Arduino's analog input pins.

Other sensors don't give you a varying output voltage per se, but instead change their resistance. Examples in your kit are the force sensitive resistor (FSR) and the bend or flex sensor. It is easy to get a changing voltage based on a changing resistance through a voltage divider circuit (Wikipedia page). The idea is that you put two resistors in series between power and ground: one that changes resistance (your sensor), and one of a known, fixed resistance. At the point in between the two resistors, you can measure how much the voltage has dropped through the first resistor. This value changes as the ratio of resistances between variable and fixed resistors change. More formally:

- potentiometer:

- force-sensitive resistor (FSR):

Try both circuits. Test the resistance range of your sensor. If you want 2.5 volts to be the middle, make the comparison resistor (33k in the diagram) the "average" value of the FSR's resistance. Test this with a multimeter.

- Bend Sensor

Thresholding with a Range Sensor (Optional)

Thresholding is the process of turning continuous data into a discrete yes/no decision.

To learn about thresholding, we'll connect the IR range sensor. The circuit is trivial: just connect red to 5V, black to ground, and yellow to analog input A0.

Take a look at the data the sensor returns with sensor_graph_02 - when the field of view of the sensor is clear (no obstacle - point it at the ceiling), it returns a low voltage. Move your hand high over the sensor, then start lowering it - you should see the output voltage rise, until you are about 4" away. The sensor has a range of operation of 4"-30".

Let's do something useful with that data. Imagine a smart cookie jar that reminds you not to snack in between meals. We could put an IR ranger into the lid. Whenever a hand comes too close, our program could play a warning sound or flash a warning light. Write a patch to manage this!

Tilt control with an Accelerometer (Optional)

In this example, we'll simulate the motion of a ball on a tilting plane in software and control the tilt through a sensor. Think of it as a first step to build your own electronic game of Labyrinth. The right sensor to use is an accelerometer. Accelerometers can report on both static and dynamic acceleration -- think of static acceleration as the angle the accelerometer is held with respect to the ground (the acceleration measured here is due to gravity). Dynamic acceleration occurs when you shake the sensor.

The accelerometer in your kit is a 3-axis, +/- 1.5-6g accelerometer sensor (1g is the acceleration due to gravity). You will have to solder on 0.1" header pins to fit this into the breadboard. The connections you need to make are Vin to 5V power from the Arduino , G to ground, and Xo, Yo & Zo to the first three analog input pins on the Arduino board. My default, the acceleration range is set to +/- 1.5g; you could solder on the gsel jumpers if you want less sensitive/greater range with +/- 6g.

Now, get a feel for the data the accelerometer provides. Use the Light Dimmer presets, which will track analog values on A0 and A1. Then pick up the Arduino+accelerometer board and tilt it in various directions. Start by holding it so that the accelerometer board is parallel to the ground. Find in which direction the X reading increases and decreases; do the same for the Y reading.

Next, change the PD patch so that you can also read the Z axis of the accelerometer.

Putting It All Together

- Create a patch to make sounds based on button and sensor values from the Arduino. You can try to adapt your patches from Lab 1, or come up with a new patch.

- Try to make a simple musical interaction. Think about music -

- does it have dynamics?

- can you turn the sound off?

- can it be expressive?

- Make a video showing your interaction! Narrate over the video to explain your design. Post your video on the Music 250a Lab Video Wiki.

(OPTIONAL) Light an RGB LED!

Included in your kit is a common-cathod RGB LED. Unlike the other LEDs, this LED has four pins instead of two. By using the Pulse Width Modulation Control, you can get the led to cycle through different parts of the colors spectrum.

Here is the schematic for the LED from the data sheet:

You can see that the longest lead is the common cathode (which should go to ground). The each of the other pins should be powered from the Arduino (ideally through PWM-capable pins) through a low-value resistor (~220 Ohm).