7745 Sensing Lab 2

This lab most recently revamped by Edgar Berdahl and Wendy Ju. Chris Carlson, possibly Bill Verplank, and others have likely contributed.

For this lab you need your Satellite CCRMA kit, a laptop computer with Ethernet adaptor to program it, and some headphones with a mini 1/8" (2.54mm) stereo jack.

You are also invited to bring the following optional items, but they are by no means required:

- Some of your favorite breadboardable sensors and LEDs.

- Your powered loudspeaker.

Power Up and Prepare Arduino

- Use the same procedure as described before to power up Satellite CCRMA and login as the user ccrma with the password temppwd.

- As always start by running the following command to stop the default pd patch from running

stop-default

- Then start pd by executing

pd &

More Analog Circuits

Now we will work with the continuous input values provided by analog sensors - potentiometers, accelerometers, distance rangers, etc

Voltage Divider Circuit

- Open the pd patch ~/pd/labs-Music-250a-2012/lab2/

- Read the messages in the pd window and make sure that it was able to open the device on /dev/ttyUSB0 (this is the Arduino -- it's showing up as the 0th serial device).

- Enable the input for analog in 0 by checking the appropriate checkbox.

- Experiment further by connecting some additional analog sensors to pins such as a0, a1, a2, a3, a4, etc. The sensors you choose should be completely new to you. Start making an entirely new musical interaction using the sensors. Some sensing circuits are shown below. For more ideas, see the sensors lecture or ask.

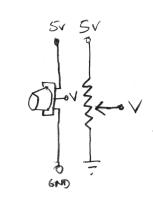

- potentiometer:

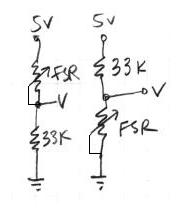

- force-sensitive resistor (FSR):

Try both circuits. Test the resistance range of your sensor. If you want 2.5 volts to be the middle, make the comparison resistor (33k in the diagram) the "average" value of the FSR's resistance. Test this with a multimeter.

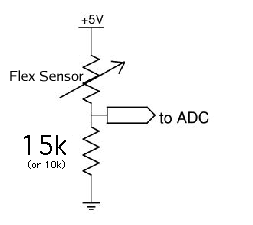

- Bend Sensor

First Digital Circuits

Build the Button and LED Circuit

We'll start our digital tutorial with three simple light circuits.

- In the first one, the LED is on all the time.

- In the second, the LED only lights up when a button is pressed and a circuit is completed.

- In the third example, we'll replace the manual switch with an Arduino pin (set to output mode), so we can control the LED from our program.

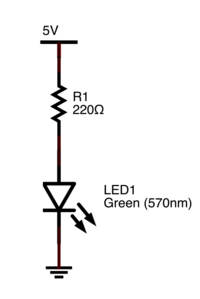

Power an LED all the time

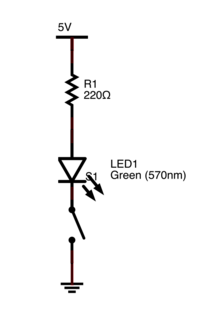

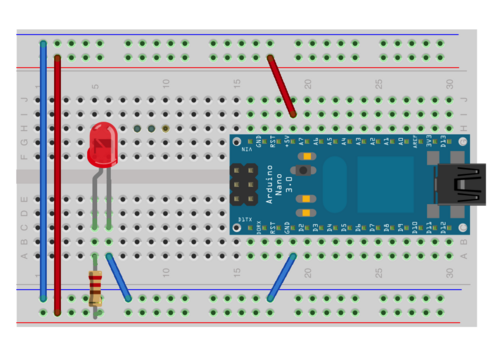

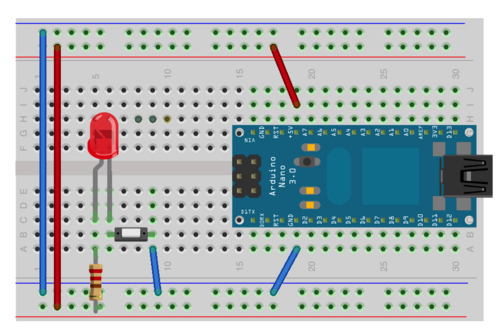

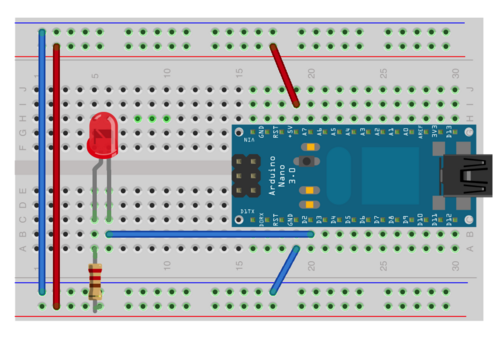

Build the following circuit on your breadboard. Use a 220 Ohm resistor (red red brown gold -- see this page about resistor color codes). Because the LED is a diode, it has a set voltage drop across the leads; exceeding this causes heat to build up and the LED to fail prematurely. So! It is generally important to have a resistor in series with the LED. Also, another consequence of the LED being a diode is that it has directionality. The longer lead, the anode, should be connected towards power (THE LONG ARM REACHES FOR POWER!!!); the shorter, cathode, should be connected towards ground. (In the diagram, the longer lead has a bent "knee.")

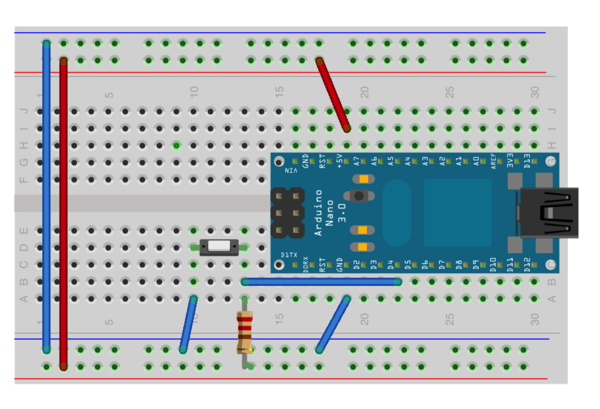

Make a light switch

Next, we'll insert a switch into the circuit. The momentary switches in your kit are "normal open", meaning that the circuit is interrupted in the idle state, when the switch is not pressed. Pressing the switch closes the circuit until you let go again.

Use a multimeter to see what happens to the voltage on either side of the LED when you press the switch.

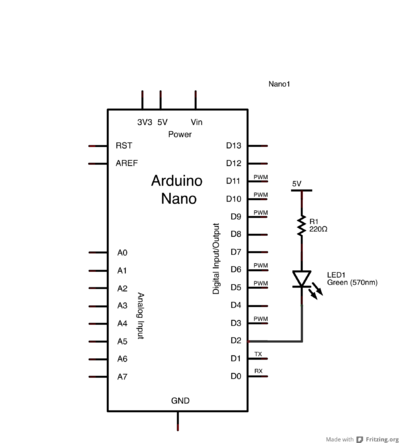

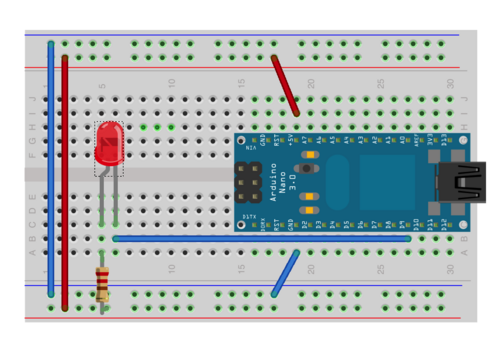

Toggling LED with Pd

In the third example, we'll replace the manual switch with an Arduino pin (set to output mode), so we can control the LED from our program. The safe way to do this is to let the Arduino pin sink current - if we toggle the pin low, it acts as ground and current flows through the resistor and the LED as it did in the previous examples. When we take the pin high, to 5V, there is no potential difference and no current flows - the LED stays off.

- Go back to the main patch and set pin 2 to output.

- Then go back to the "digital outputs" pane. When you click on the checkbox for digital pin 2, the state of your added LED should change (on vs. off).

Optional: Try changing your patch so the light stays on when you press the mouse button, and stays off when you press it again. After that, change your patch so the light blinks on/off. Then, have your patch button switch the light between on and blinking.

Sensing buttons in software

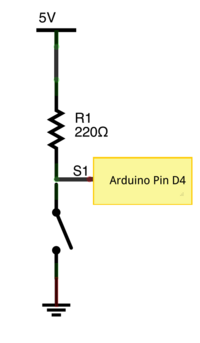

We've used code to trigger output - what about the other direction, sensing physical input in code? Just as easy. Here is a simple switch circuit:

When the switch is open, the Arduino pin (set to input mode) is pulled to 5V - in software, we'll read 1. When the switch is closed, the voltage at the Arduino pin falls to 0V - in software, we'll read 0. The pull-up resistor is used to limit the current going through the circuit. In software, we can check the value of the pin and switch between graphics accordingly.

- Setup the circuit and connect it to digital pin 4 (D4).

- Set the mode of pin 4 to input.

- Then look at the "digital input readings" pane while you press the button.

When you press the button, you should see the digital pin 4 reading change in the "digital input readings" pane.

Fading LED (Optional)

What about those "breathing" LEDs on Mac Powerbooks? The fading from bright to dim and back is done using pulse-width modulation (PWM). In essence, the LED is toggled on and off rapidly, say 1000 times a second, faster than your eye can follow. The percentage of time the LED is on (the duty) controls the perceived brightness. To control an LED using PWM, you'll have to connect it to one of the pins that support PWM output - 3,5,6, 9, 10 or 11 on the Arduino. Then write a patch that cycles the PWM values.

For instance, for a single LED connected to pin D9:

- Connect the LED to pin D9 of the Arduino using the usual circuit.

- In arduinoLab.pd, set the mode of digital pin 9 to pwm.

- In the pane for pwm/servo outputs, choose pin 9.

- Pull the analog_output horizontal slider back and forth and watch the LED get brighter and dimmer.

- Fun extension if you can find an RGB LED: Get an RGB (red/green/blue) LED (I think we may be currently out of these), connect it to digital pins 9, 10, and 11, and adjust the brightness of the three color components to cycle the LED through a rainbow of colors!

Putting it all Together

- Create a patch to make sounds based on button and sensor values from the Arduino. You can try to adapt your patches from Lab 1, or come up with a new patch. Try to make the sound good!

- Make a simple musical interaction. Think about music -

- does it have dynamics?

- can you turn the sound off?

- can it be expressive?

- After you have finished, demonstrate your interaction to Edgar to get credit.

OPTIONAL: Firmware for Rotary Encoders

- WARNING: If you do not complete this exercise all the way, you will not be able to use your Arduino anymore until you reflash the StandardFirmata sketch onto it.

- So far, the firmware StandardFirmata has been installed on your Arduino. This allows the Arduino to communicate with the arduinoLab.pd patch above. To do so, it is necessary for arduinoLab.pd and the Arduino to exchange information back and forth. They do this over a serial connection via USB. In order to encode the data to go over the serial connection, StandardFirmata uses the Firmata standard.

- However, sometimes Firmata is not sufficient for a project. This is usually true when you want the Arduino to do something besides obtaining physical input, sending physical output, or transmitting data over the USB serial connection.

- On your kit, start the Arduino software by typing the command arduino & in the terminal. Please upload the following firmware programs from your Arduino program's Examples folders to your Arduino controller and see how they function. Do attach LEDs, buttons, as is appropriate:

* Examples->Digital->Blink * Examples->Digital->BlinkWithoutDelay * Examples->Digital->Button

Custom Communication

One reason that you might want to program the Arduino microcontroller is to enable greater control over the communications from the Arduino. In this segment of the laboratory, we learn a wider variety of ways to send data from the Arduino hardware to the computer than we have previously used.

Serial communication with the Arduino Serial Monitor

You might have noticed in the previous lab segment that it can be very hard to know what is going wrong when the Arduino hardware is in autonomous mode. Here, we send serial communications between the Arduino hardware and the Arduino IDE.

- Examples->Analog->Smoothing: Use the Serial Monitor (icon on the far left on the Arduino IDE toolbar) to get data back from the Arduino. When you do this, you'll notice the TX light on the Arduino lights up and stays lit.

The high datarate on the Serial monitor can make the Xwindow for the program freeze. If the Arduino IDE crashes, go to the main terminal and type 'fg' to bring the arduino to the foreground, and then type 'cntl-x, cntl-c' to kill the program. Now add a delay to the loop function to prevent the freeze. What size delay makes for speedy updates but doesn't cause freezing?

- Examples->Communication->SerialCallandResponseASCII. This will show you how to do two-way communication with the Serial Monitor.

Serial communication with PD

Now let's try using serial to communicate with pd.

Low-latency sensing

Encoder input

- Download the example firmware encoder.zip for interfacing a rotary encoder and then transfer it from your computer to your Raspberry Pi kit using CyberDuck or a similar method.

- Then, on your kit, uncompress it by running the command

unzip encoder.zip

- Enter the encoder subdirectory by executing

cd encoder

One final reason that you would want direct control over the Arduino firmware is that you might have very low-latency sensing needs. As an example of this, we show you here how to use encoder input with the Arduino.

- Quit Pd to ensure that Pd isn't using the USB/serial connection to the Arduino.

- Start up the Arduino software using the command arduino & and upload the sketch ~/encoder/encoder/encoder.ino to the Arduino. Then quit the Arduino IDE and start up Pd and open the patch ~/encoder/encoder.pd

- Now you need to build this schematic to interface the encoder: http://cm-wiki.stanford.edu/mediawiki/images/c/c1/Encoder_filter.png.

Pin two is the middle pin on the rotary encoder, and pins 1 and 3 are the other directly adjacent pins. It can be a bit difficult to plug the encoder into the solderless protoboard, but you can do it if you straighten out the pins first.

Note: In the schematic, AVR Phase A is digital pin 2 or the Arduino, and AVR Phase B is digital pin 3.

Now you're ready to send out the position of the encoder over the serial bus. The values should start near zero and increase or decrease, depending on which direction you turn the encoder. How are negative numbers represented? Why does the encoder always start near 0 when the program on the Arduino is restarted?